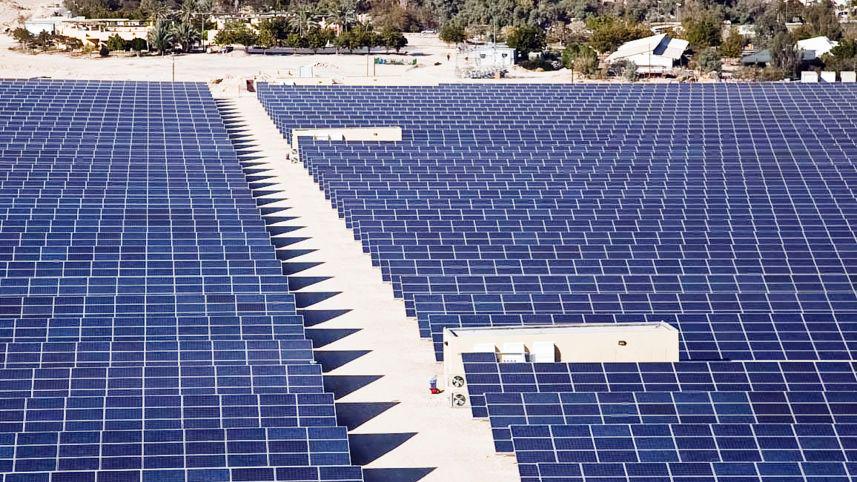

The solar fields would dot the Jordanian desert, while Israel would supply water, says environmental organization EcoPeace.

With an abundance of sunlight most of the year and decades of knowledge, Israel should be a light unto the nations in everything regarding solar power. But research suggests that it’s the nations that will shed light upon Israel, which currently draws only 2 percent of its electricity from renewable energy.

And the research, conducted by environmental groups and academics, suggests that regional cooperation could be bolstered in the mix.

The formula involves solar fields in the Jordanian desert supplying electricity to Israel and the Palestinian Authority. In exchange, Israel would provide its neighbors with water.

Such cooperation seems particularly relevant; ahead of the climate change conference in Paris, Israel pledged to reduce the amount of greenhouse gases it emits.

EcoPeace, which includes Israeli, Jordanian and Palestinian researchers, presented the initiative on Thursday at the Tel Aviv-based Institute for National Security Studies. A member of the project’s steering committee is Prof. Eytan Sheshinski, who headed a special panel on taxing Israel’s natural resources.

According to the initial findings, solar facilities can be placed over hundreds of square kilometers in Jordan, providing a hefty chunk of the electricity the kingdom and its neighbors need. To supply a fifth of the electricity Israel will need by 2030, 195 square kilometers will be necessary. That would cost $16.5 billion, but it’s 30 percent less than the cost of electricity to Israeli consumers today.

The research was conducted with funding from the Adenauer Foundation in partnership with the Israel Energy Forum.

“We believe the cost of establishing solar fields in Jordan will decline because there will be assistance from countries around the world,” said Gidon Bromberg, the Israeli director of EcoPeace Middle East.

According to the findings, to overcome the expected water shortage, Israel will have to nearly double the amount of water it desalinates to 1.1 billion cubic meters per year. Two desalination plants would operate in the Gaza Strip for the local population, and Jordan would desalinate in a plant it’s building near Aqaba.

“There are places in Amman where water is supplied just once a week, and people collect water in pails,” Bromberg said.

Israel already supplies water to Jordan from Lake Kinneret and recently expanded the agreement. Bromberg says there is stubborn opposition to such agreements; nobody wants to become dependent.

But according to EcoPeace, cooperation would be rooted in mutual dependency because it’s impossible to desalinate or deliver water without electricity.

“Israel has desalination technology and access to the Mediterranean Sea, which is its advantage,” Bromberg said. “In contrast, Jordan has wide expanses of desert where it’s no environmental problem to build large solar fields.”

EcoPeace played an important role in crafting a plan to rehabilitate the southern Jordan River, which the Jordanian and Israeli governments endorsed.

The new plan faces an uphill battle. The proposed desalination plants are at odds with the Israel Water Authority’s decision to cut back on desalination. Another hurdle is the Israel Electric Corporation’s claims that it’s difficult to integrate solar energy into the country’s power grid.

If cooperation does get underway, it could not only cut down on greenhouse gases but also increase political stability in Jordan, currently the home to hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees.

Moreover, safe supply of water and electricity could substantially improve the quality of life of Palestinians, especially Gazans. By bringing in Jordan, Palestinians would be less dependent on Israel.

“Water and energy are cross-border issues, so cooperation is important,” Sheshinski said. “I think the right way to do this is not through quotas for each side but through joint and judicious usage.”

Originally posted on Haaretz by Zafrir Rinat

Photo courtesy of Albatross Aerial Photography