In partnership with CSIRO and the Australian National University (ANU), a local technology company Dyesol has designed a new form of solar photovoltaic (PV) cells that exclude rare earths and silicon metals.

Dyesol claims that the new solar panels are bound to become a global technology disruptor. The secret to the innovative technology is perovskite, a unique material that was originally discovered in the mid-19th century in Russia’s Ural Mountains.

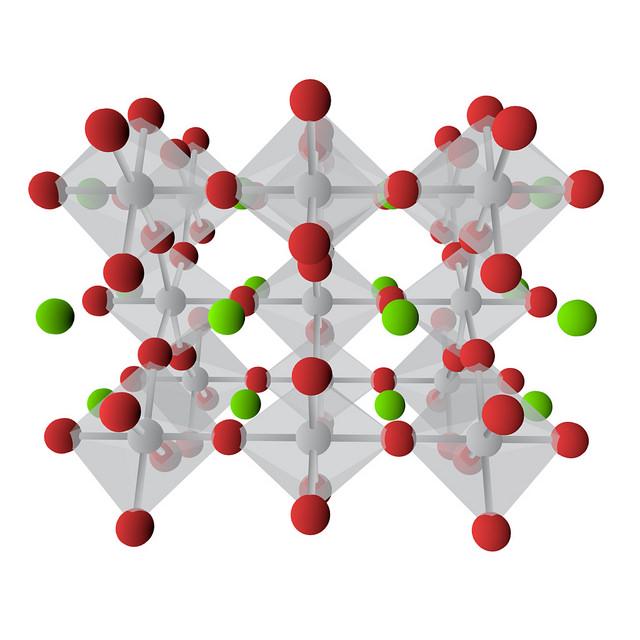

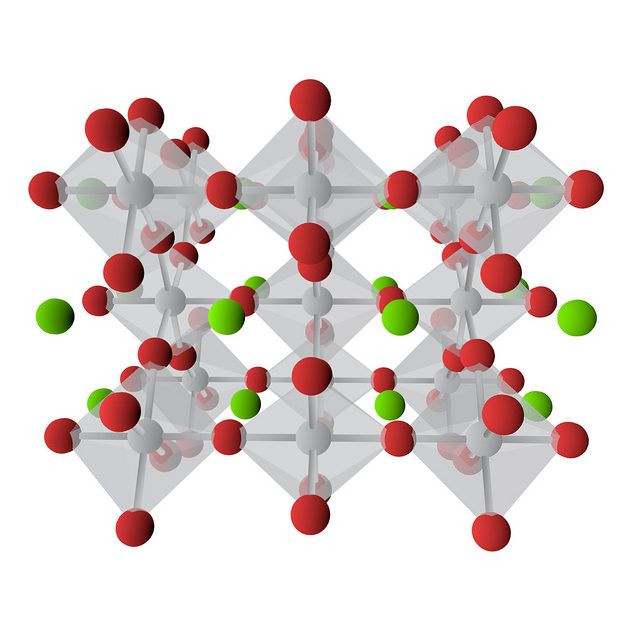

Richard Caldwell, the managing director of Dyesol said perovskite was a general name used to refer to the entire class of compounds with a chemical lattice structure, which were really great at harnessing energy and converting it into a seamless flow of electrons.

Mr. Caldwell added that the third-generation of solar panels was not just about panels, but could also be integrated in building materials too.

“Perhaps things like roofing material, windows, and facades,” he said.

“So you embed this material at the time of initial manufacture and you have a building which is effectively solar-enabled.

“It’s also got some additional functionality which is the generation of electrons, commonly known as electricity.”

There have been other perovskite-based solar photovoltaic cells in the last decade, but these latest ones have a greater ability to convert sunlight into electricity.

Removing silicon metals from the equation makes the cells ecologically friendly on their own.

“The production of silicon metals is generally quite heat intensive,” Mr. Caldwell said.

“You have to raise the temperature to 1,122 degrees Celsius to refine the material to get it to a level, which means there’s a lot of embedded energy in the existing technologies.

“That goes against the grain because the idea is to produce cheap, clean and green technology that leaves a minimal carbon footprint.”

This comes with economic benefits too.

“Silicon-based solar PV probably has a payback period of around two and a half years, whereas the payback period [recouping of costs] in these new technologies, including perovskites, is about three to six months,” Mr. Caldwell added.

The perovskite-based solar PV will be suited for various applications to be determined by geography.

“Places like Northern Europe, for example, they’re not very suited to silicon metals, so our technology has what’s known as a low-light premium, which means it performs quite well in low light conditions,” Mr Caldwell said.

“Or in areas where they have haze or pollution, silicon depends very much on direct exposure to the sunlight; it’s very dependent on the angle of the sun, and it is relative to the sun itself.

“And countries in Northern Europe, and the UK, are a good place for us to set up our market entry strategy.”

IMAGE via Edumol Molecular Visualizations