The world of technology is ever evolving, and the latest research findings confirm that Germany’s Massive Nuclear Fusion Machine is in fact real, with an amazing potential to harness the Sun’s power.

For the first time in 2015, Germany fired up a new version of massive nuclear fusion reactor, which successfully withstood a burning blob of hot helium plasma.

Since then, there have been concerns regarding the state and performance of the device and whether it was really working as expected. These concerns are valid to say the least considering that this machine has the potential to maintain controlled nuclear fusion reactions in future.

Thankfully, a team of US and Germany based researchers have shown a green light to all these concerns confirming that indeed the Wendelstein 7-X (W 7-X) stellerator generates twisty, super-strong, 3D magnetic fields expected of it’s design, along with an “unprecedented accuracy“.

According to the researchers, the design had an error rate of less than one in 100,000.

“To our knowledge, this is an unprecedented accuracy, both in terms of the as-built engineering of a fusion device, as well as in the measurement of magnetic topology,” the researchers published in Nature Communications.

Even though that doesn’t sound that cool, it’s critical since the magnetic field is designed to trap hot plasma balls which have to be long enough to ensure nuclear fusion occurs.

Currently, nuclear fusion is fast emerging as one of the most promising clean energy sources available.

Producing just a little more than salt water, nuclear fusion offers limitless energy using the same chemistry that powers the Sun.

Nuclear fission and nuclear plants are totally different. And while nuclear fission is generated from existing nuclear plants and works by splitting an atom’s nuclear into tiny nuclei and neutrons, nuclear fusion produces massive energy levels when atoms are fused together at extremely high temperatures.

And there are no radioactive wastes or other byproducts produced at the end.

Just like the sun’s longevity, nuclear fusion also boasts incredible potential to supply planet earth with sustainable energy for as long as humanity will need it – but of course only if we figure out how to harness its reaction.

It’s worth noting that the ‘if’ in this case is the hard nut that scientists have been trying to crack all this while— more than 60 years to be precise, and it’s obvious that we’re still far from our goal.

The most challenging part of this whole process is the fact that achieving controlled nuclear fusion entails recreation of conditions inside the Sun.

Ideally, this means setting up a powerful machine which can actually produce and control a 100-million-degree-Celsius (180 million degree Fahrenheit) ball of plasma gas.

This is easier said than done. However, there are some designs for nuclear fusion reactors around the world that are already operating and doing the best to deliver on their design expectations.

These include the W 7-X; a highly promising attemps.

Instead of using a 2D magnetic field to control plasma–the technique commonly used by the more popular tokamak reactors, the stellerator generates twisted, 3D magnetic fields to power its operations.

This works effectively by allowing stellerators to control plasma without necessarily requiring the use of an electrical current; which tokamaks depend on. This in return renders stellerators stable, as they can still work even when the internal current is disrupted. Well, that was the main reason for its design.

Further testing

Despite helium plasma being successfully controlled by the machine in December 2015, and the more complex hydrogen plasma in February 2016, no finding had revealed that the magnetic field was truly working as expected.

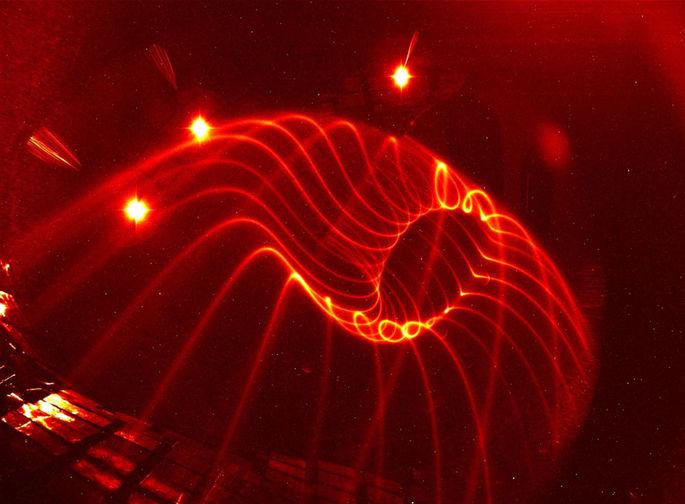

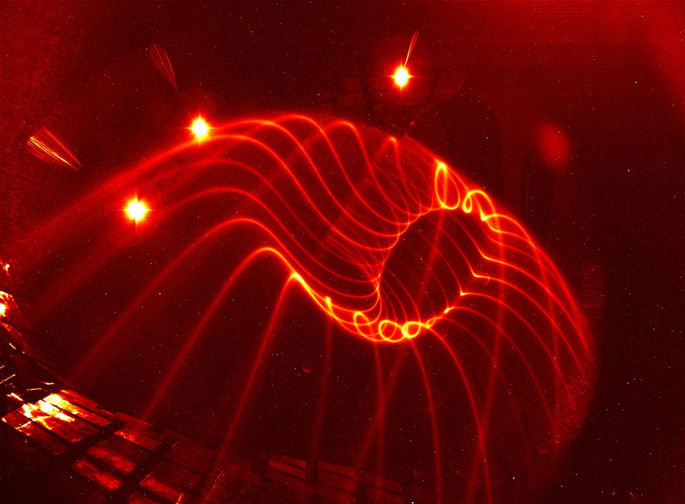

This was confirmed when a team of researchers from the US Department of Energy and Germany’s Max Planck Institute of Plasma Physics launched an electron beam along the reactor’s magnetic field lines.

The team then used a fluorescent rod to sweep through those lines, creating light in the shape of the magnetic fields. The result was actually the exact type of twisted magnetic fields the design was supposed to produce.

“We’ve confirmed that the magnetic cage that we’ve built works as designed,” said Sam Lazerson, one of the chief researchers from the US Department of Energy’s Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory.

Even with such groundbreaking success, W 7-X wasn’t designed to generate electricity from nuclear fusion – it simply proofs the concept that indeed it _could _work.

The reactor is expected to start using deuterium in place of hydrogen come 2019 to generate actual fusion reactions within the machine, but won’t have the potential to produce more energy than it currently requires in operating efficiently.

We are hopeful that the next-generation of stellerators will overcome this challenge. “The task has just started,” explain the researchers in a press release.

Of course, this won’t happen tomorrow but is definitely a major milestone in the world of nuclear fusion, with the common W 7-X officially taking France’s ITER tokamak reactor head on-both of which have the capability to trap plasma long enough to allow fusion to take place.

So the big question is, which machine will be the first to generate efficient power from nuclear fusion for humanity? We all just can’t wait to find out.

IMAGE via NATURE COMMUNICATIONS